Video game development is a tougher job than people might think, with the pervasiveness of working practices like crunch prompting a global movement towards unionisation. But for Rasheed Abueideh, a Palestinian software engineer who makes games in his spare time, there are additional challenges.

“Living here in Ramallah, or in Gaza, it’s difficult. Any minute you could be killed on the road because there is always a gun loaded and pointed at your head. I am in the office in Ramallah, so usually when there are clashes near us we work with tear gas around us, and we are crying. And we call that ‘work under pressure’.”

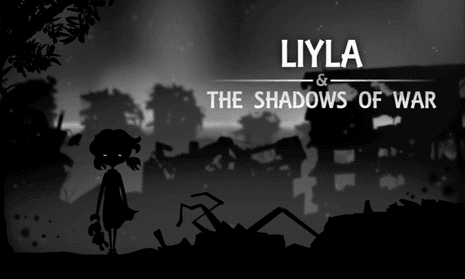

Abueideh is the designer of Liyla and the Shadows of War, a short mobile game in which the player character helps his wife and daughter, Liyla, escape from Gaza. Liyla is fictional, but the game features real events: strikes on schools, the death of four children playing on a beach. When Liyla was first released on the App Store, Apple refused to categorise it as a game, feeding into a historical precedent that Apple prefers games to be frivolous.

The game ends with Liyla’s death. “I would be cheating if I made a different ending,” Abueideh says. “This is what’s really happening, and this is what I really want everybody to know.”

Abueideh is a father of four young children himself. Sometimes, when holding one of them in his arms, he has flashbacks to images of other Palestinian parents holding their child’s dead body. When he let his children play Liyla, they asked him: “Why did they kill her? She did not do anything wrong.” “And I couldn’t answer that,” he says. “I made the game, and I don’t have an answer for that.”

Abdullah Karam, a Syrian refugee living in Austria, also wants children to play his game. Path Out is an episodic autobiographical adventure developed by Causa Creations, in which the player leads Karam through his escape from Syria. As well as starring as the protagonist, Karam features in occasional video clips in the corner of the screen, YouTuber-style, narrating the events and providing context. With his quips of “there you go, dead again,” Path Out has a lighter tone than Liyla.

“We wanted to share a perspective with the player that kind of makes them laugh, although the subject is pretty serious,” says Karam. “We wanted to build a connection.”

In the game, Karam is 18 years old, fleeing Syria at his parents’ behest to avoid joining the military. “You can see how much of a kid I was,” Karam says. “Like, they would tell me, ‘Pack your most important stuff,’ and I would ask them, ‘Can I take my Xbox with me?’”

In the first episode of Path Out, the tasks evolve from finding a lamp when the electricity goes off to navigating borders, landmines and Isis. Karam and the developers wanted to use the relationship between player and player character to help people understand what it’s like to be a refugee.

“That’s why the game is free,” he says. “To share this perspective and to tell everybody, no matter how much of a bad image you have in your head about refugees, here’s another one.”

To learn more about why Rasheed Abueideh and Abdullah Karam chose to use video games to share their stories about life in Palestine and Syria, listen to the Guardian’s digital culture podcast Chips With Everything: ‘Developing games in a war zone’.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion